Called Me Here on Monday Kid Quill

Idea control, similar birth control, is best undertaken every bit long every bit possible earlier the fact. Many grown-ups volition obstinately persist, if only now and and so, in composing pocket-sized strings of sentences in their heads and achieving at least a momentary logic. This probably cannot be prevented, only we accept learned how to minimize its consequences by arranging that such grown-ups will be unable to pursue that logic very far.

~Richard Mitchell, Less Than Words Tin can Say

In January of 1977, New Jersey'southward Glassboro State College (now Rowan University) saw the publication of a new campus journal. Sporting handset type and quaint nineteenth century line-drawn imagery, information technology was called the Underground Grammarian . On the front page of the first edition of the 4 page newsletter, the anonymous editor printed its "Editorial Policies":

The Hole-and-corner Grammarian is an unauthorised journal devoted to the protection of the Mother Tongue at Glassboro Land College. Our language can be written and even spoken correctly, fifty-fifty beautifully. We do not demand beauty, merely bad English cannot be excused or tolerated in a higher. The Surreptitious Grammarian will betrayal and even ridicule examples of jargon, faulty syntax, redundancy, needless neologism, and any other kind of outrage against English.Clear language engenders articulate thought, and clear idea is the near important benefit of education. Nosotros are neither peddlers nor politicians that we should prosper by that utilise of language which carries the to the lowest degree meaning. We cannot honorably accept the wages, conviction, or licensure of the citizens who employ us as we darken counsel by words without understanding. And so, to the whole college community, to students, to teachers, and to administrators of every degree, the Underground Grammarian gives

The newsletter's self-declared "Wandering Scholar" provided examples and corrections. On the final page, he offered subscription information:

There are no subscriptions. We don't lack money, and we may attack you in the adjacent event. No one is safe.We will impress no messages to the editor. Nosotros will requite no infinite to opposing points of views. They are wrong. The Underground Grammarian is at war and will give the enemy zip but battle.

Nine issues of the Clandestine Grammarian were published that first year. In issue four, the writer provided a P.O. Box for letters, queries, and cursory comments on grammatical matters. "Horrible examples gratefully accepted." Issue eight revealed that a member of the staff, ane R. Mitchell, "has been promoted to the post of Assistant Circulation Manager."

Thus began a 15-twelvemonth odyssey by an initially obscure professor of English language, Richard Mitchell, one of the great and forgotten metaphysical minds of the twentieth century. He was the homo who awoke me to the idea that, fifty-fifty though I was a published writer with a B.A. in English language, I had yet to acquire how to tell reason from rubbish.

* * *

Richard Mitchell conceived his historic newsletter the year I entered college. Built-in in Brooklyn in 1929, Mitchell spent his early years in Scarsdale, New York. He met his wife Francis while briefly attending the University of Chicago. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the Academy of the S and earned his Ph.D. at Syracuse Academy. After instruction college English in Defiance, Ohio, he became a professor of English (later of Classics) at Glassboro in 1963.

Nearly 20 years later, the failure of my secondary instruction became credible in a university Spanish grade during which, for the first time I could recall, I learned about prepositions. In the mid-1970s, I was a straight-A high school sophomore elevated into Honors History and Honors English. In history, we learned about neither American history nor Western civilization, but rather about the Bantus of Southward Africa, a noble study. In English, we did not learn much virtually writing and grammer, and were instead left to be our open up and creative selves. Nearly all of my bored fellow honors students indulged in pot, mescaline, and speed.

My Spanish class experience made me angry. I felt cheated. I had started community college studying computer programming. After publishing an commodity in a computing magazine, I transferred to a four twelvemonth university with the assumption an English degree was my ticket to becoming a professional writer. I was right. But, more importantly, that shift had taken me from my science and math roots into the earth of Shakespeare and Austen, Socrates and Augustine. I perceived a glimmer of what it meant to have a classical liberal educational activity.

My first upper division English course shocked me when a dinosaur English professor, Dr. David Bell—a professor in Richard Mitchell's mold, but not yet a curmudgeon—gave me my first C on a paper, busting my A-student cocky-image. That wake-upwards call helped me to run across that, although I was published, I had much to larn near writing. Worse, in my first graduate course, Bell's "Austen and Bronte," I discovered that I had much to larn almost reading, and that I lacked the acuity to appreciate Jane Austen'southward clear, witty, and precise prose.

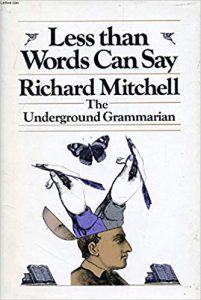

Not long before, I'd read Richard Mitchell'southward first volume, Less Than Words Tin Say. I don't call up how I stumbled upon him. I'd probably read some opinion cavalcade that referred to his work. In a publication annunciation in the Underground Grammarian, Mitchell described information technology every bit "a melancholy meditation on the dismal consequences of the new illiteracy."

He had wanted to championship the book The Worm in the Brain, pointing to the dangers of authoritative rhetoric. The publisher rejected that championship as "as well frightening and grisly," Only I knew I had institute a fellow traveler when I read his Foreword:

Words never fail. We hear them, we read them; they enter into the mind and become part of the states for every bit long as we shall live. Who speaks reason to his boyfriend men bestows it upon them. Who mouths inanity disorders thought for all who listen. There must exist some minimum allowable dose of inanity beyond which the mind cannot remain reasonable. Irrationality, similar buried chemical waste, sooner or afterwards must seep into all the tissues of idea.

With that prophetic book, I first experienced the "cleansing fire [that] leaps from the writings of Richard Mitchell," as George F. Will later on described it.

Mitchell did title the first affiliate "The Worm in the Encephalon," in which he told the story of a colleague who would ship him a note whenever there was some committee coming together. At outset the note read something like, "Allow's meet next Monday at ii o'clock, OK?" Simply when he aspired to become assistant dean pro tem, the simple, perfect prose changed. "This is to inform you that there will be a meeting adjacent Mon at 2:00." After achieving that appointment, the note read, "Yous are hereby informed that the committee on Memorial Plaques will meet on Mon at two:00." The worm in the brain had done its piece of work.

I began to notice the worm in the brain during my everyday interactions with friends and colleagues at the academy, especially the English professors. It ofttimes took the form of a label which created an image in the brain that prevented thought. Ane such professor, smart and engaging, returned a paper analyzing a passage in the U.S. Constitution. She gave the paper an A, but added, "I tin't help just feel that your argument is wrong, although I tin can't explain why. I showed it to my married man, and he thought that it was a conservative statement."

That argument invalidated the A, and I experienced my start taste of how subtly an abstract label tin paralyze an otherwise thoughtful mind. Years later on, while teaching at a business college, I saw a more than pronounced form of the same phenomena. During a Concern English class, I chatted with a vivid pupil who volunteered for the NAACP. We would discuss all kinds of interesting topics, such as the similarities and differences between Martin Luther Rex and Malcolm X.

That is, until I noticed a change. She had stopped talking to me like a fellow human being being and started talking at me like a white male. I stopped her and asked if she noticed what she had but washed. She hadn't, so I pointed out that she had shifted from talking to me to talking to an epitome within her head. I told her that I would hold my hand upwards and block my face up every fourth dimension she did information technology. Every bit the chat proceeded, and I raised my hand, lowered it, and so raised it once more, she became aware of the worm in her brain, a mental-emotional implant that prevented her from treating me as a colleague when sure topics were engaged.

Her implant was creating rubbish, of course, merely information technology was insidious past nature because information technology disguised itself as something in the existent earth. Worms in the brain are like that.

* * *

My academy library subscribed to the Underground Grammarian, and I apace caught upwards with the starting time ix years of its 15 twelvemonth run. In its second upshot, Mitchell clarified the newsletter's goal: "The Hush-hush Grammarian does not seek to brainwash anyone. We intend rather to ridicule, humiliate, and infuriate those who abuse our language not and then that they will do better only so that they will finish using linguistic communication entirely or at least go away."

For the start 8 years, Mitchell used a Chandler & Toll rattle-and-clank printing printing that was over seventy years old and required the time consuming use of hand-set up blazon. In year nine, he discovered the Macintosh figurer and desktop publishing. While albeit that the transition was painful and that he would miss the taste of lead, he decided that "Our proper business is to get this affair out, and not to preserve a fine and ancient craft."

The newsletter proved popular enough that his publisher Little, Chocolate-brown, and Visitor released a collection titled, The Leaning Tower of Babel and other affronts from the Surreptitious GRAMMARIAN . I of my favorite essays in the collection, entitled "The Answering of Kautski," begins:

Tyranny is always and everywhere the same, while freedom is always various. The well and truly enslaved are undecayed; nosotros know what they will say and call up and do. The gratis are quirky. Tyrannies may be overt and violent or covert and insidious, only they all crave the same thing, a field of study population in which the ability of the give-and-take is dulled and, thus, the ability of thought occluded and the power of act brought depression.

Mitchell went on to hash out Vladimir Lenin'southward views on education, logical thought, and his contempt for people, and how the educationists of his day were conscious and unwitting agents of that tyranny.

Having read everything Mitchell published, I recognized my growing sensitivity to academic and media thoughtlessness. I grew queasy at how pervasive vague and meaningless language had become amongst professors, fellow students, the media, cocky-serving public servants, and especially professional educationists. A fellow graduate student who had started a teacher training program to be a high school teacher reported back on the thoroughly insane postmodernist requirements of the curriculum. However, he confessed that he was going to keep his head downwards and complete the program without resistance.

What educationists were doing to educational activity was the topic of Mitchell'south 1981 volume, The G r aves of Academe. The infiltration of inanity into the public schools had already struck Mitchell'due south disemboweling spirit: "Clear language," he wrote, "engenders clear idea, and clear thought is the nearly of import do good of education." He connected:

Schools do not fail. They succeed. Children e'er acquire in school. Always and every twenty-four hour period. When their rare and tiny compositions are "rated holistically" without regard for separate "aspects" similar spelling, punctuation, capitalization, or even organization, they learn. They learn that mistakes bring no consequences.After sober and judicious consideration, and weighing i matter confronting another in the interests of reasonable compromise, H. 50. Mencken ended that a startling and dramatic improvement in American teaching required but that we hang all the professors and fire downwardly the schools. His uncharacteristically moderate proposal was not adopted.

The question for me after reading The Graves of Academe was this: Was anyone not already on board persuaded to have action? Was Mitchell'southward just some other voice in the wilderness?

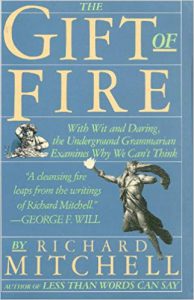

Mitchell's greatest achievement was his 1987 volume The Gift of Fire. In the Introduction, he reviewed his function equally satirist and the "ancient and honorable task" of the "castigation of fools." Just something had changed. Now he pondered doing good, and the extent to which he knew what the good was. Although he had heard virtually doing good, he realized that he had not known information technology. "True education is not knowing about, it is knowing."

I decided every bit a Teaching Assistant to use this book equally the reader in my English language 1A Freshman Composition course. My aim was simple. Students embarking on a four year pedagogy might find value in thinking about precisely what kind of education options they had. Are they in that location for the grades alone? The partying? Are they willing to ponder the difference between a liberal education and vocational training, which Mortimer Adler aptly described every bit that betwixt "the didactics of gratuitous men" and "the educational activity of workers and slaves"?

The Gift of Burn down is full of wisdom:

Who kickoff called Reason sweet, I don't know. I suspect that he was a homo with very few responsibilities, no children to rear, and no payroll to meet.

and

If you lot should prefer to understand that children are those homo beings who have not yet found the grasp of their own minds, then the task you take given yourself, that task of rearing a child wisely and well, is all of a sudden transformed from indoctrination to pedagogy, in its truest sense, and made not only possible but even likely—provided, to be sure, one little prerequisite, which is that yous are not a child, that you take come into the grasp of your listen.

and

Here is a truth that most teachers will not tell you, even if they know it: Practiced grooming is a continual friend and a solace; it helps y'all now, and assures you lot of help in the future. Adept education is a continual pain in the cervix, and assures you always of more of the same.

The Gift of Fire highlights Socrates, Epictetus, and Jesus as role models for true education. The final chapter, "How to Live (I think)," is a reflection on how each of united states is ever in a state of becoming. As such, Mitchell cannot tell anyone How to Live. He can, withal, set out what he believes to be the "largest and simplest definition of a truthful pedagogy… It is all that is absent-minded in the lives of those who aren't composing How to Live (I recollect)."

The book inspired me to find new ways of challenging my Freshman English language students. I devised an exercise to respond the question, "If the government were to offering you millions of dollars on the condition that you give up admission to all history and the arts before 1960, would you lot have?" Students who chose not to take the money would stand up on i side of the room. Those who chose to have it would stand on the other. The undecided would sit in the centre as the rest would try to persuade them to come to their side.

The students were evenly divided, with only a handful in the heart. I'll never forget 1 young man who struggled with the class, his writing barely passable. He sat in the middle with a serious look on his face, while students effectually him had fun trying to persuade him to accept their side. At i betoken he looked up at me and said, "This is really important, isn't information technology?" I responded, "Information technology's probably one of the most important decisions y'all volition ever make."

* * *

In 1996, I received an email from Richard Mitchell, five years later he had closed the Hush-hush Grammarian. Information technology read simply, "What are you lot doing?"

The year before I had created the Hugger-mugger Grammarian website, using optical recognition software to scan his out-of-print books and make them freely available online. I chosen it an "Unauthorized Site Dedicated to the Preservation of the Works of Richard Mitchell." It was while I was uploading the newsletters I had, and requesting missing issues from other readers, that I received Mitchell's email. He had already given permission to re-create or plagiarize his writings in one of the newsletters. But did that extend to his books?

Happy but horrified by this first contact, I explained that I wanted to make his works freely available to teachers and anyone else who wanted to enjoy them. But, if he preferred, I would remove the entire site. I did request donations from readers to help keep the site alive, just no donations were required to enjoy free access to the site'south content. He replied that he was fine with the work I had done, only as long as I kept information technology freely available. I breathed a sigh of relief, and nosotros embarked on an occasional correspondence.

In one electronic mail, I told him about how I used The Souvenir of Burn down in class, and mentioned the do I conducted and the young human being who had asked nearly the importance of his decision. Mitchell responded, "You succeeded in creating an occasion for instruction." This was a description he had used in The Gift of Burn.

I cannot say that Mitchell taught me reason from rubbish. More accurately, from his lucid writing I caught the ability to tell reason from rubbish. I learned that he, besides as Dr. Bell, among others, burned with a cleansing burn down that cleared away some of the dross within me. I learned that great teachers create an environment where truthful didactics is caught, not taught—the occasion of education—and that we now live in a earth with fewer and fewer great teachers.

* * *

Richard Mitchell died at his abode on December 27, 2002. A memorial was held at the academy where he had taught all his life. I published a call for stories from readers who knew Richard Mitchell to mail on the site, and the messages I received are a attestation to the affection with which he is remembered and the influence he had upon those his writing touched.

Today, in a world awash with emotional reactiveness and churlish rubbish that crowds out precious reflection and reasoned conversation, I anguish for the wry humour and penetrating insights of the homo who concluded his life so far to a higher place ground—Professor Richard Mitchell, the one and only Underground Grammarian.

Quillette Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.

Source: https://quillette.com/2019/06/10/how-the-underground-grammarian-taught-me-to-tell-reason-from-rubbish/

0 Response to "Called Me Here on Monday Kid Quill"

Post a Comment